No More Masters

It's time to change your Git repo's default branch.

In my book Git for Humans, published in 2016, I made a lot of references to master — naturally, as it’s been the default branch name in Git for a long time. Like many people, I simply accepted that master meant “master copy” and didn’t look at it too closely.

But now it’s 2020, things are changing, and there are other, better names for our primary Git branches that don’t indirectly invoke slavery.

My work friend Una made the practical argument for renaming (to main, which the community seems to have adopted as the new standard):

For me, having a master branch is like realizing a cute geometric pattern on some old part of my house is made of swastikas, or that the old statue outside the main library in my hometown is actually a Confederate monument that had stood there for 115 years. Removing symbols of racism isn’t nearly enough, but that doesn’t mean don’t remove them.

People have to live in a Git-based world, and Git does not make that easy. Folks are talking about renaming branches like there’s just a box you can check. For new projects, it’s almost that easy — in fact, GitHub has announced they will change the default for everyone later this year. But existing projects need a bit more work, as I’ll explain.

Like I said, my book mentions master a lot. (Like, a lot a lot.) It seems likely that within the next few years this will seem like a really stale choice, so I am talking to the awesome team at A Book Apart about updating Git for Humans’ text and examples to favor main as the default branch name.

They’re pretty busy, and there’s still a pandemic happening, so no ETA on when a book update might ship. But it’s in the works!

For now let’s start with what you need to do to start new projects out on a main branch if your tools don’t yet treat that as a default.

Naming your first branch

One of the great things about Git is that it doesn’t really require your main branch to be named master (or anything else). You can choose any name you want, and you can change names at any time as long as you’re willing to do some work.

When you start a new repo, Git is hard-coded to set the first branch’s name to master. But that branch doesn’t technically exist until you make your first commit. So here’s what you do to set your preferred name on a brand-new repo:

git init # if you hadn't done this yet

git checkout -b mainUntil GitHub finishes changing the default primary branch name, you’ll need to go into your repo settings there to tell it that main is your primary branch; you’ll find instructions for how to do this later in this post.

“Renaming” an existing branch

Behind the scenes, everything in a Git repo is immutable. When you make commits, it only looks like you’re changing files and directories in your project — really, you’re just adding new versions of things on top of the old ones.

In other words, you can’t actually rename a branch in Git, because renaming would be mutating data, which Git tries to never do. But you can create a new one and (optionally) get rid of the old one, which is basically the same thing.

Here we’ll replace a master branch with a new one called main, pointing to the current head commit:

git checkout master # if you're not already there

git checkout -b mainAlternatively, you can use git branch to ask Git to create a new branch pointing at the same commit master is on:

git branch main masterWhichever way you do it, your master branch will be left intact, you’ll have a new main branch that’s identical to master.

To make this new main branch available to your collaborators, push it to GitHub:

git push -u origin mainUpdating your primary branch in GitHub and other tools

Next, let’s tell your tools that there’s a new primary branch in town.

GitHub

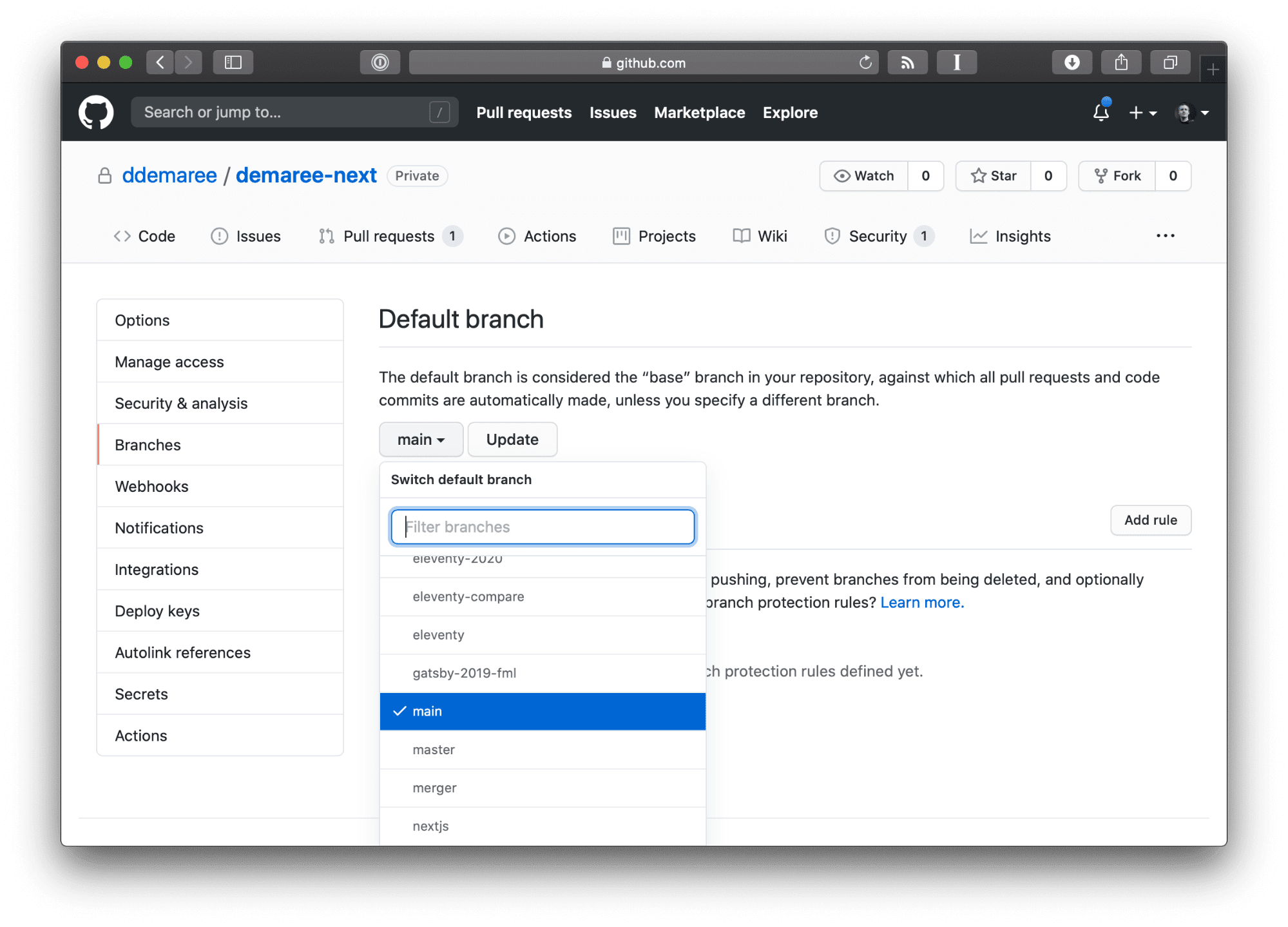

Open your repo page on GitHub while signed in, and click on the Settings tab, then click Branches in the left-hand navigation. Once you’re there, on the right-hand side you’ll see a drop-down that lets you change the name of your default branch.

Once this is set, new pull requests will automatically be set up to merge into main, and git clones from GitHub will also check out main by default.

Netlify

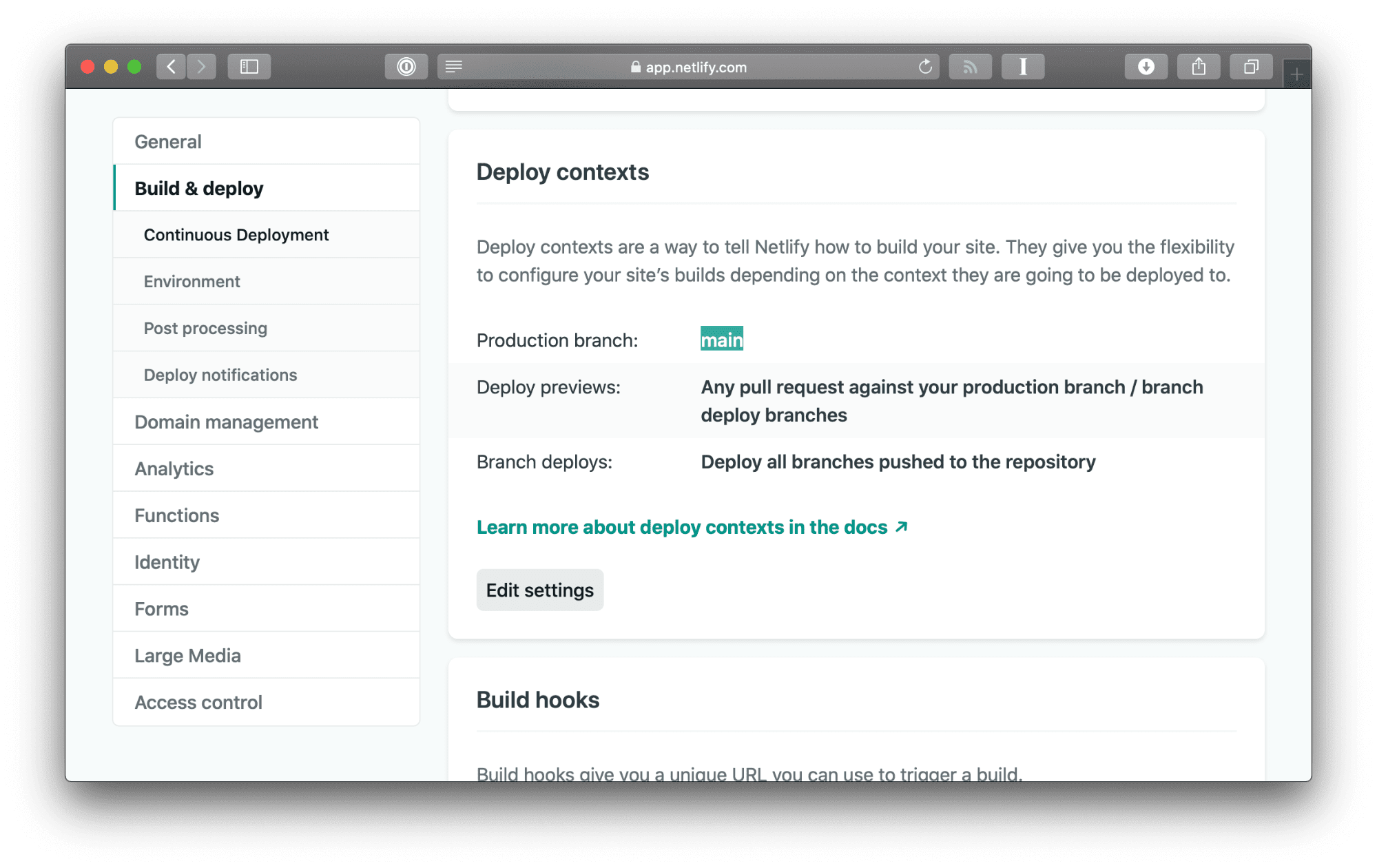

If you (like me) use Netlify to host your websites and JAMstack apps, and use their GitHub integration to automatically publish changes after you push them, you’ll need to go into your Netlify site settings to select a new production branch. This is under Build & deploy > Deploy contexts.

What about other integrations?

The value of changing your primary branch name right now is inversely proportional to the amount of time and effort you have to put into it. Eventually, we want a name like main to be the new default for every project, no marginal effort required. For small or relatively simple projects, it’s low-cost enough to do now, or soon, while it’s front of mind.

The master branch is a load-bearing element. Many systems and workflows depend on it, and the more tools you have hooked into your repo, the more work it will take to change names without ruining someone’s day. If you have complex integrations tied into Git, you should approach this with the same care you’d approach any other infrastructure change.

What you want to avoid is a situation like the one in this tweet by Bryan Liles:

Moving to main signals that we want to be inclusive. It’s meant as a welcome mat for underrepresented folks who may collaborate with us, now or in the future. But moving away from master breaks things now. Adopting a new branch name really is a cosmetic change, and though I think it’s ultimately the right thing to do, as long as you ultimately will do it, it’s OK to take your time and get it right.

Deprecating your master branch

This last section, and I cannot stress this enough, is for people who have carefully considered the impact of changing from master to main, and are ready to burn their ships and never look back.

Sadly, Git doesn’t have any such thing as “branch redirects,” and though GitHub has some special features to “protect” branches from receiving pushes, vanilla Git does not. Once you’ve decided to get rid of master, you may want to make it so that syncing with it fails, with a note explaining what to do instead.

So you may want to replace your old master with an “orphan” branch, which (as the name implies) is a branch/commit with no parent, completely detached from the rest of your Git repo’s history.

We’ll name this new orphan branch no-masters. To start, we call on git checkout --orphan, which asks Git to start a new branch but intentionally forget anything about your former head commit. This is similar to if you were starting over with a brand-new repo.

git checkout --orphan no-mastersYou’ll end up with a branch that contains all the files and folders from your project, but staged as if they were new additions.

Next, we’ll remove all the content from this branch. Using git rm (as opposed to regular ‘ol rm) will only delete files and folders that are checked into Git, leaving behind ignored content.

git rm -fr .Depending on your tech stack, this may leave behind some stuff that had previously been hidden by .gitignore, all of which will now show up when you run git status. So we’ll restore the old gitignore file from main to make sure these files are not committed or deleted:

git checkout main .gitignoreFinally, let’s leave a note explaining why this branch is empty. We’ll add and commit a README.md Markdown file with the following text:

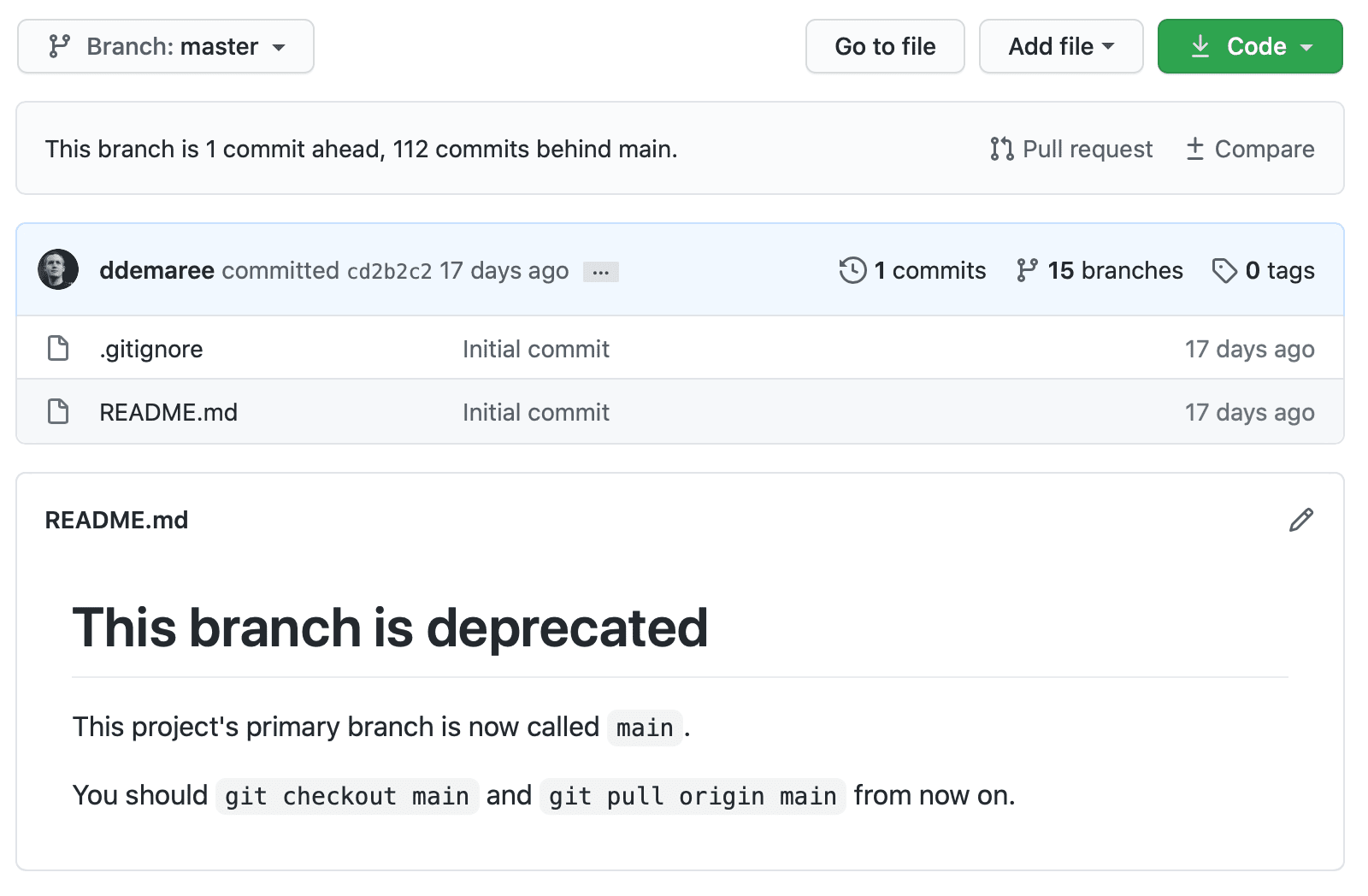

# This branch is deprecated

This project's primary branch is now called `main`.

You should `git checkout main` and `git pull origin main` from now on.Then commit these changes:

git add .gitignore README.md

# … output deleted …

git commit -m "Deprecation message for `master` branch"Because this is an orphaned branch, if you run git log you’ll only see this commit, none of the history before it:

git log --oneline

> cd2b2c2 (HEAD -> no-masters) Deprecation message for `master` branchOK, now for the scary part — replacing master with this content. Which means deleting your old master branch:

git branch -D masterThis will delete master locally, allowing you to create a new masterbranch that points to this new, empty-except-for-deprecation-message commit.

git branch master no-mastersIf you were to then git checkout master, you’ll see the deprecation message.

git checkout master

git log --oneline

> cd2b2c2 (HEAD -> master) Deprecation message for `master` branchWhew. Okay. One last step: pushing this master branch to GitHub. Because this is a new, orphaned branch, you will need to force-push. This may (hell, probably will) break any integrations you have hooked up to master, so you may want to wait until your team and infrastructure are fully migrated over to main until you do this.

git push -f origin masterAhhhhhhhhh, so nice to have that done. Here’s the deprecation message as shown on one of my GitHub repos:

Because the server’s master now points to this orphaned commit, Git will raise an error whenever you or someone on your team tries to pull from it:

git pull origin master

From <your-repo-url-here>

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

fatal: refusing to merge unrelated historiesIf only it was this easy to break free from history in real life.